School Mariachi Programs As Catalysts Of Change

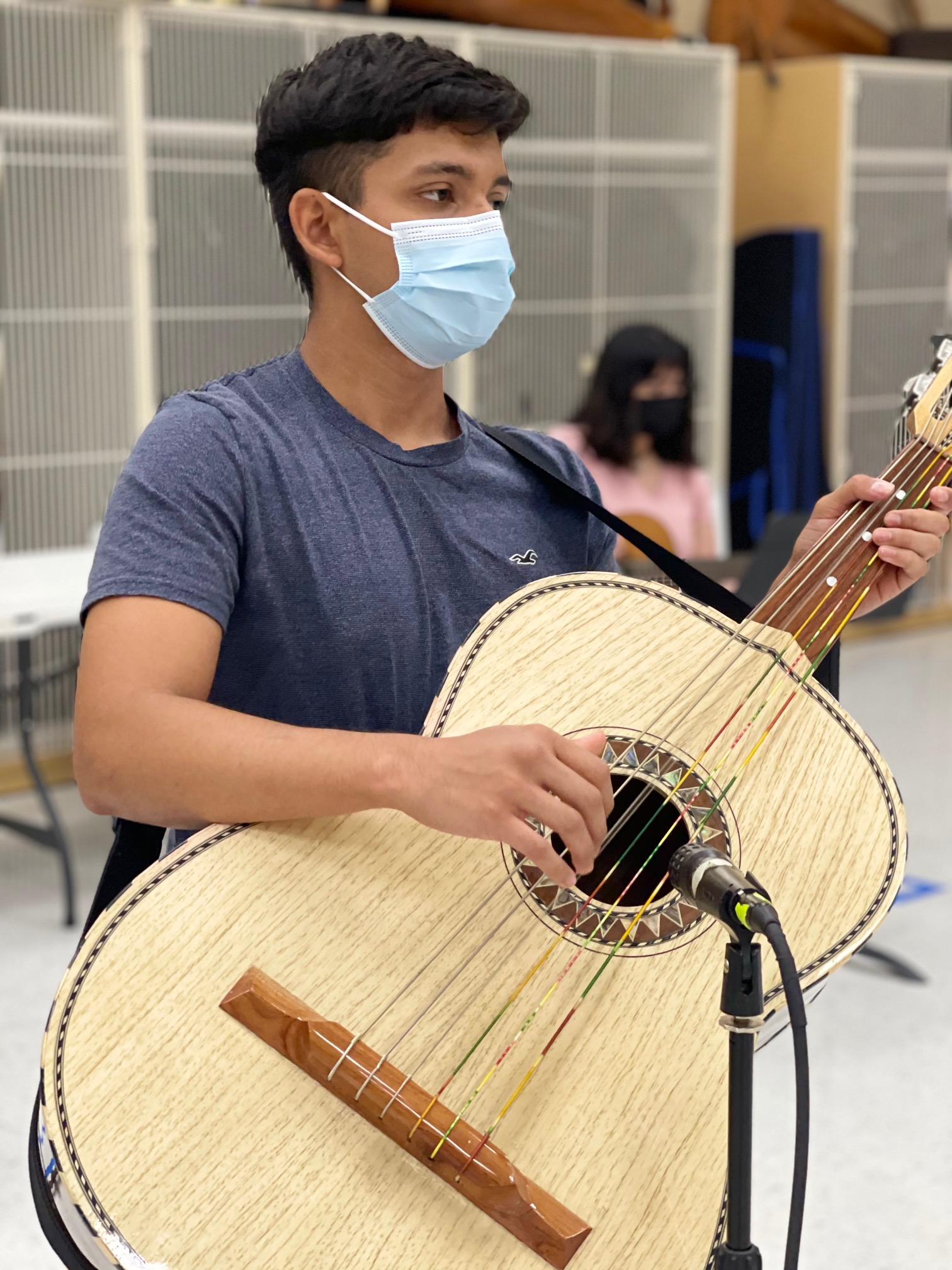

The strident, joyful notes of guitars, vihuelas, guitarrones, violins and trumpets playing in unison are increasingly heard through the hallways of public middle and high schools, as Mariachi programs become more and more popular across the country. Students of all backgrounds are drawn to this quintessentially Mexican music genre, which consists of an ensemble of at least eight musicians, as well as several singers or at least one soloist.

Mariachi music originated in rural Western Mexico as far back as the early 18th century, but became a symbol of Mexican culture in the post-revolutionary period, when it appeared in classic films and was associated with the charro (cowboy) tradition. Over time, Mariachi bands expanded their repertoire of songs from the original sones to include corridos, boleros, ranchera songs and even contemporary pop and rock music. Mariachi music has been present in the American Southwest for at least a century, and courses have been taught in public schools since the late 1960s, in Los Angeles, San Antonio and South Texas. Since the 1970s, many U.S. universities have had their own nationally and internationally recognized Mariachi ensembles. In 2011, Mariachi was recognized as Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO, and it has evolved into an international phenomenon.

Mariachi programs have grown exponentially in U.S. public schools over the past 30 years, from just a handful of programs in a few states to more than 500 today. There are numerous Mariachi Conferences, Festivals and Competitions that showcase hundreds of student Mariachi bands and attract audiences of thousands. A large number of Mariachi education programs are still found in the traditionally Mexican-American Southwest, but also in large Hispanic districts in states across the country.

Educators agree that Mariachi programs are powerful catalysts of positive change: they transform schools, Hispanic/Latino communities around schools, students (Hispanic and non-Hispanic alike), teachers, and even the broader field of music education.

What makes them such a powerful tool for school improvement and student success? To gather insights on Mariachi programs’ benefits, Hispanic Outlook reached out to several of today’s most dynamic Mariachi educators: Music Educator Marcia Neel is a Mariachi curriculum and professional development expert who has built up the Clark County School District’s Mariachi Program in Las Vegas (now the largest in the country), and conducted National Mariachi Workshops for Educators that have trained teachers from more than 250 programs. Ramón Rivera has directed the award-winning Mariachi Huenachi at Wenatchee High School in Washington State for 14 years, has directed the Mariachi Northwest Festival, and is currently Director of the Mariachi Program at Mount Vernon High School. John Contreras has founded and directed the award-winning Mariachi Aztlán at Pueblo High School in Tucson for the past 20 years, and recently received the 2021 Arizona Governors Arts Award for Arts in Education. Mayra Alejandra García has directed the award-winning Mariachi Los Lobos at La Joya ISD Palmview High School in the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas for the past 21 years and has founded her own all-female group, Mariachi Mariposas. DePaul University professor Dr. Barbara Radner has been curriculum development consultant for the Mariachi Heritage Foundation, directed by César Maldonado, which supports Mariachi programs in Chicago Public Schools.

The benefits of school Mariachi programs

It is a well-researched fact that music programs in general contribute to students’ success at school: Marcia Neel affirms that they improve attendance and build concrete literacy, math, creative and critical thinking skills that are transferrable to other disciplines. Ramón Rivera emphasizes that “kids involved in any music have a positive outlet. A kid who picks up a violin or a guitar won’t pick up a weapon or get involved in negative things”. So what makes Mariachi programs especially valuable? All the Mariachi educators we spoke with emphasized two key aspects:

1. Mariachi programs build strong communities, both within school and beyond it.

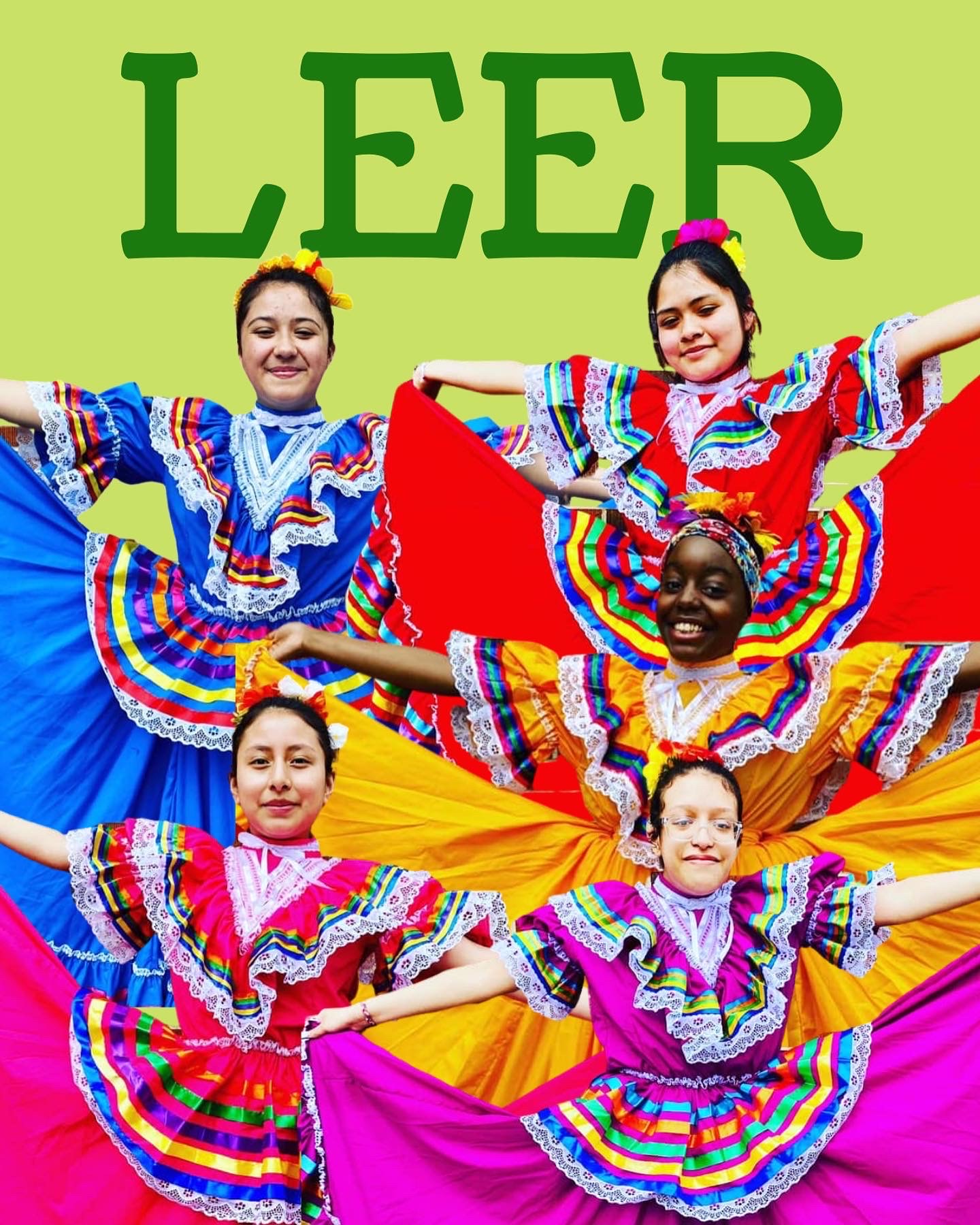

They do so, firstly, by giving Mexican American (and other Latino students) a sense of cultural pride and belonging. Instead of feeling lost in high schools that can often seem vast and impersonal, the Mariachi group gives students a sense of “being someone” and having a voice. For García’s students in South Texas, “wearing a Mariachi suit with sparkly gala not only became part of the performance, it also became a second skin of authenticity,” of pride in their identity. In Chicago, Radner observes that “a Mariachi program improves self-esteem”, a key part of socio-emotional learning, to a greater degree than a standard music class.

Since the ensemble requires constant teamwork, Latino students form strong bonds with other members of the group, Latino and non-Latino alike. Non-Latino students are drawn to the versatile Mariachi program because it plays not only traditional Mexican music but also many other modern genres. In Rivera’s words, “Mariachi is not only for Mexicans – students can play music from Pedro Infante to Bruno Mars, from Pedro Vargas to Ariana Grande.” Neel adds that the Mariachi’s energy is infectious: “when other students see the Mariachi kids having so much fun, they want to be part of it!”

In addition, Mariachi classes are mostly taught in English, but naturally have songs in Spanish and use many Spanish terms, which provides a comfortable bilingual learning environment for everyone: recently arrived English Language Learners, second or third generation Latinos who may only speak a bit of Spanish, and non-Latino students who can learn more Spanish. Although 94% of the Tucson ISD is Hispanic, Contreras emphasizes that around 70% of these students don’t speak Spanish at home, so the Mariachi class provides a “bilingual benefit”.

Thus, Mariachi programs promote the integration of students within the school. In Neel’s words, “they become a mosaic, a place for cross-cultural exchanges”, which improves the overall school climate.

Secondly, Mariachi programs have a strong impact beyond the school walls. All the educators interviewed described Mariachi music as “intergenerational” and emphasized that Mexican American Mariachi students become more integrated with their own families as they play the music that their grandparents or parents identify with and love. Contreras sees this as one of the most powerful impacts of a Mariachi program: “I see it happen all the time: students play Las Mañanitas for their Abuelita on her birthday, and the overwhelming emotional response makes something click… then they’re hooked, because they’ve made a deep connection with their own family.”

It follows that Latino families make stronger connections with the school through Mariachi programs. Bailes folklóricos (traditional dances) are often offered as well, which add yet another layer of tradition and pride. Neel observes that Mariachi programs “bring parents in the door” to meet with teachers. In Chicago, Radner emphasizes how proud family members are when their children play in the school Mariachi, and how validated they feel. In addition, when Mariachi programs improve the general school climate, stronger ties are made to the local community overall, including non-Latinos.

2. Mariachi programs build excellent music, academic and leadership skills, providing many avenues for a successful future.

Curricular, credit-bearing Mariachi programs require discipline and perseverance, and motivate students to attend school regularly, work hard and do well in other classes. Some Mariachi teachers require that their students maintain a high overall GPA in order to remain in class or participate in performances, boosting their overall achievement. The academic results are often impressive: according to Neel, drop-out rates decreased dramatically in some Clark County Schools after implementing Mariachi programs.

In addition, challenging themselves to play or sing well, earning the right to wear the full traje de charro and presenting themselves before large audiences strengthens students’ self-confidence. In Contreras’ words, “When students hear an audience clapping, when they get standing ovations, they can see very clearly that their hard work has paid off…they are instantly motivated.” They also “understand how to present themselves” confidently: “when a student was nervous about a job interview, I reminded him that he’s stood up on stage, sometimes in front of thousands of spectators!”

Mariachi programs are not only about music – they are consciously designed to foster leadership skills and to give students exposure to the outside world. “The art [of Mariachi] should be a vehicle of mobility” for the students Rivera works with in Washington State, many of whom are children of agricultural workers. “We want them to become leaders in their community”, he continues, describing the ways in which performances locally and nationally have opened students’ eyes to a world of possibilities. Indeed, Mariachi Huenachi has performed with top stars and gone to Washington D.C. to play for Congress. For Contreras, one of the Mariachi program’s key effects on students is that it “broadens the scope of their world” through travel to performance venues ranging from concert halls to universities and stadiums with top stars.

All of these factors help students to graduate from high school with good prospects for the future.

Their work discipline, higher GPAs, leadership skills, and exposure to the outside world help them to enroll in higher education. Educators gave numerous examples of Mariachi students who have gone on to become doctors, teachers, scientists. Mayra García proudly states that “the programs that saved at-risk students [in her South Texas district] are now producing valedictorians, salutatorians and Ivy League bound students.” One of the most quoted examples of Mariachi programs’ success is Richard Carranza, who began as a Mariachi teacher in Tucson and then went on to become Chancellor of Public Schools in San Francisco, Houston and New York City.

The Mariachi programs Rivera has directed offer some privately funded scholarships to help students with college fees, as does Contreras’ Pueblo High School in Tucson. In addition to these often modest scholarships offered by high schools themselves, there are some scholarships available from external foundations and colleges.

Mariachi students also become skilled musicians and performers. As Neel mentions, they are very well qualified to apply for nearly any music scholarship, and they can also become versatile music teachers. Once they graduate from high school, students can start their own local bands, and earn good money for paying college fees by performing for family functions and local celebrations. This work is certainly more satisfying and “more lucrative than flipping burgers”, in Contreras’ words. He adds that the current rate for a Mariachi performance is around $350 per hour.

Those students whose Mariachi bands progress towards winning awards at state and national competitions acquire networks of contacts with musicians across the country, and may become distinguished performers themselves.

The post-pandemic future: advice for starting new school Mariachi programs

As the pandemic subsides in many parts of the country, Mariachi programs are beginning to return to in-person rehearsals or hybrid learning, following covid protocols specific to music programs.

What advice do the experienced Mariachi educators we interviewed give to school and district administrators who may be considering opening a Mariachi program, post-pandemic?

1. There are many ways to find funding, particularly through current federal assistance. Programs are often funded by local community organizations, foundations and businesses. Most of the money for the trajes de charro and instruments are raised from the High School Mariachi’s own performances. Most notably, the Federal CARES Act provides sizable grants to schools for a variety of purposes. Contreras stated that his district bought $1 million worth of instruments, which helps to meet the covid protocol that instruments cannot be shared.

2. Mariachi programs should be curricular and standards based. In order to truly keep students engaged in the program and at school, it must be a rigorous and credit-bearing course. Neel and other authors have created curriculum materials that offer useful guides. Mariachi programs that meet high arts program standards draw more students to the overall field of music: Contreras believes that Mariachi programs must challenge students and “raise the bar” for other music programs.

3. Mariachi instructors should be professionally trained and licensed. Mariachi players may be great musicians, but they must be good at teaching, as well. Neel’s workshops for Mariachi educators strengthen their pedagogical training, and she emphasizes the need for Mariachi musicians to become licensed educators, after they have been appropriately trained.

4. The rewards will be invaluable for the entire school. The effects of Mariachi programs ripple outward from students to schools and communities. As Rivera concludes, Mariachi programs are a “golden ticket” to positive school change.